Clover Lawns: Is the Trend Lucky for Pollinators?

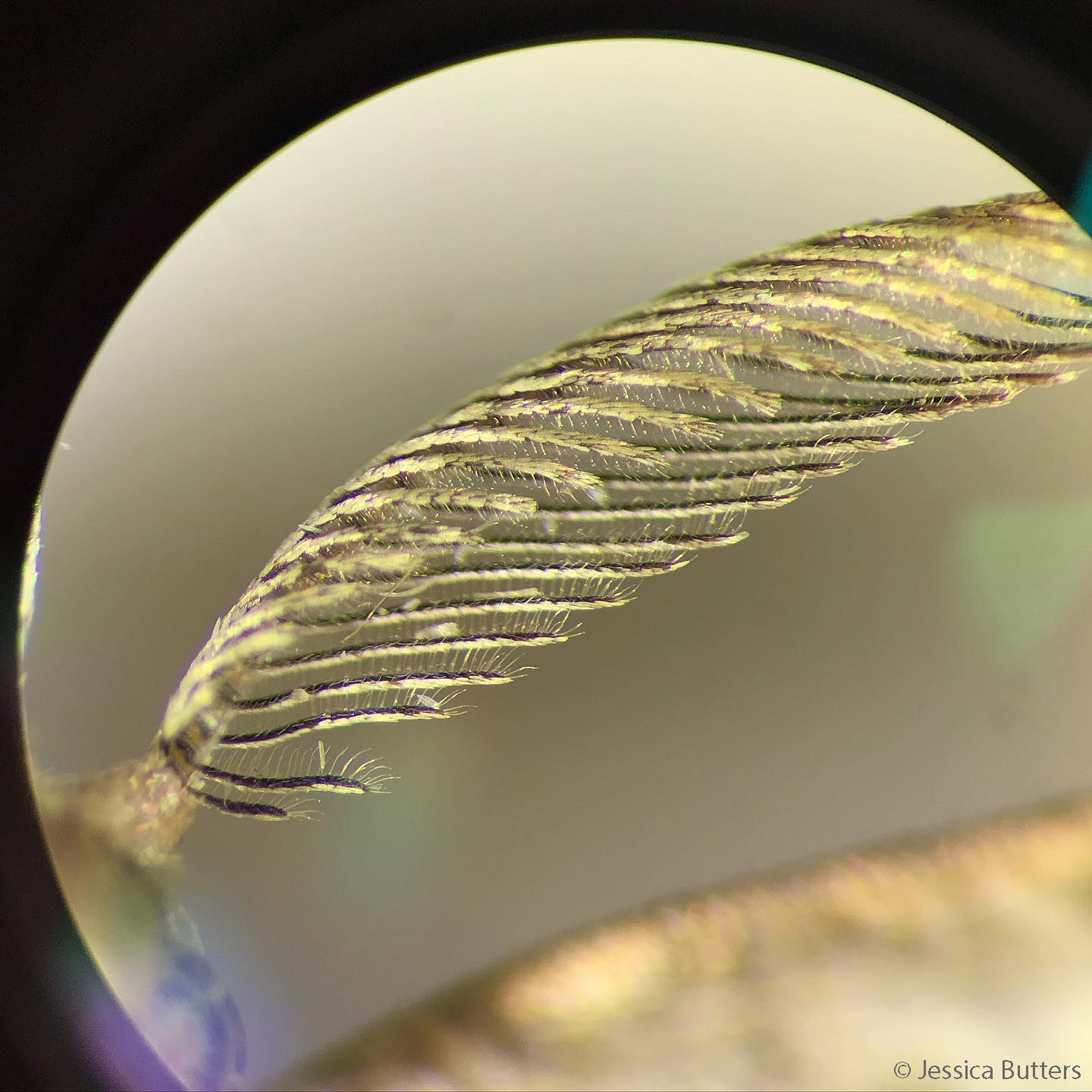

A honey bee visits a clover flower.

The idea of creating a pollinator-friendly yard is finally taking root, and the notion of a perfect lawn, along with its expense, is being weeded out. Clover lawns are one of the latest trends yard owners are trying out in an effort to be more environmentally conscious. This new kind of lawn is often touted to support pollinators, require less up-keep, and lower pollution. But do they live up to the hype?

What is a clover lawn?

What constitutes a “clover lawn” has several renditions. The simplest form of a clover lawn is a lawn in which someone passively allowed clover to establish and grow. They stopped spraying herbicides, mowed less, and allowed grass to die in areas, giving way to clover and other plants. A second kind of clover lawn is one in which clover was actively seeded into the lawn, over the existing turf (this was a common practice until the 1950s). A third way of creating a clover lawn is to kill and remove all turf and replace it entirely with clover, resulting in a uniform lawn.

Common clovers used for lawns are nonnative, including white (Dutch) clover (Trifolium repens) and strawberry clover (Trifolium fragiferum), both hailing from Eurasia. Strawberry clover is also the species included in the Scotts®Turf Builder® Clover Lawn seed. The idea of seeding mini or micro clovers is increasingly popular. These clovers are normally short-statured cultivars of the species listed above. Micro clover lawns are supposed to require even less maintenance and have smaller flowers that attract fewer bees. There are no readily-available native clovers that are marketed for clover lawns (though there are some fantastic native clovers in Iowa).

Why would you want a clover lawn?

Those interested in clover lawns will have different objectives. Some are drawn to the fact that most clovers require less care than turf grasses (though they still require regular maintenance). Clovers usually need less mowing, resist weeds, many are drought- and shade-tolerant, and they also fix nitrogen in the soil, eliminating the need for fertilizer. These attributes are also welcomed by those looking to reduce carbon emissions and pollution by requiring less mowing, herbicides, and fertilizers. Lastly, wildlife lovers hope to support pollinators with clover due to the fact that their flowers can attract honey bees and some native bees. However, keep in mind that these positive attributes are good only in comparison to a traditional turf-grass lawn, which provides scant (if any) environmental benefits and requires a lot of maintenance. Additionally, clover does not stand up to heavy foot traffic as well as grasses, and may need to be reseeded every two or three years.

Do clover lawns benefit pollinators?

Simply put, some clover lawns can provide benefits to some pollinators. If you really want a clover lawn, the best method for wildlife (and your wallet) is to passively allow clover to enter your lawn. This practice requires you to mow less and stop using herbicides, which will keep pollinators in your area healthier.

While there are some benefits to having a clover lawn, they are small from a broader point of view. At the end of the day, adding clover to your lawn adds a few species of nonnative plants in your area, which often provide sub-optimal nutrition to native pollinators. Keep in mind that many pollinators are specialists and will not visit nonnative clover. Additionally, it may be difficult to keep the clover on your own lawn, and out of natural habitats. In contrast, planting a pollinator garden, even a small one, adds multiple native flower species and provides high-quality habitat to native pollinators. Planting within a garden also doesn’t require you to rethink your entire lawn. Finally, a garden is a stronger challenge to the status quo, as planting a diverse and beautiful garden is a lot harder to be annoyed about than nonnative dandelions and clover in your front yard. It is better PR for pollinator habitat: a neighbor with a more traditional mindset for a lawn will not appreciate the spread of “weeds”, but may be open to the idea of creating their own native plant garden.

Are clover lawns worth it?

In my personal opinion, ideas such as clover lawns challenge the current lawn standard, but are not the end goal. They also do not entirely live up to the hype: they still require maintenance, and are not the seed-and-forget or “let it go” solution that many were hoping for. From this point of view, you might as well grow native plants.

From an environmental standpoint, we need more native habitat and less lawn, whether it’s traditional or clover. It would be a more effective and meaningful trend to encourage people to grow “micro gardens” for pollinators instead of praising micro clovers and other nonnative lawn alternatives. To make the biggest impact in your corner of the world, ending pesticide use and planting a native plant garden (even a tiny one!) is best. However, if that kind of project is not possible for you at the moment, ending all pesticide use and choosing to mow less often is definitely “better than nothing”. Doing so will probably invite clover into your lawn, which will suffice until you can start a small garden. The clover trend is not lucky for all pollinators, but a garden that includes native clovers could be!

A sweat bee visiting a native clover.